Prediabetics come in a variety of shapes.

We’re plump, willowy, healthy heft for our height, bursting

out of our clothes—let’s face it, we’re all over the scale when it comes to

weight.

Prediabetes is increasing in the population, as is abdominal obesity. But the increase in waist size in this country cannot be blamed for all cases of prediabetes.[1]

Keep that in mind when you’re thinking about your lifestyle and what needs to change. If you’re a person with normal BMI (body mass index) and a healthy waist size, but you’re prediabetic, you still need to look at your diet.

[Check with your healthcare provider and nutritionist before making changes to your way of eating.]

All of us living with prediabetes need to look at our diet.

By definition,[2]

we’re considered prediabetic because our blood sugar levels are higher than

normal, and that sugar comes from the foods we eat.

Don’t waste time looking for the definitive guide to eating

healthy and getting out of prediabetes land. We’re individuals with varying

genes. What works for one person may not work for another.[3]

That doesn’t mean you give up on adapting your diet. There is a path to healthy eating with your name on it, and you will find it.

What’s On The Menu?

Here are a few rules that apply to all of us:

- leave sweets (pie, cake, cookies, candy, donuts,

etc.) out of the grocery cart, try berries or fresh fruit

- pass by the white rice, instead pick up brown or

wild rice

- say no to soda pop and fruit juices, drink more

water

- don’t add sweeteners to your foods or drinks,

such as white sugar, brown sugar, agave nectar, maple syrup, or honey

- hold off on eating foods made with white flour,

such as bread, pizza crust, and dinner rolls

Other no-nos are out there, but it’s a good starting point.

How many carbs, and how much protein and fat should you eat

each day? That depends on how your body handles food.

First, talk to a nutritionist/dietitian who also has

experience or training in diabetes education. They’ll create a game plan for

you that will get you started on a healthier way of eating.

Second, buy a meter and “eat to your meter.” The nutritionist will give you a guide that applies, in general, to lots of people. It may be adapted somewhat to meet your specific medical needs, if you have any.

But without doing genetic tests on you, and conferring with

a geneticist to interpret the results, the pamphlets or info sheets the

nutritionist hands you won’t drill down to your body’s specific needs.

We want our blood sugar levels to be normal, not elevated. To get there, we must test the foods we eat to find out what our dietary triggers are . This is why we strongly recommend that for the first six months or so of adapting to your new way of eating, you use a meter to test your blood sugar levels before and after eating and first thing in the morning.

Eventually, you’ll recognize what foods work for you and

what foods send your blood sugar bouncing up. It’s going to go up after you

eat, but you want it to come back down within a certain range after a couple of

hours.

Where to start? Carbohydrates, or carbs, are a good starting

point. They’re the fuel we use to power our bodies, but we want the good fuel,

not the crappy hard-on-the-body fuel.

Generally speaking, complex carbs are good, simple carbs are

bad.

The dietitians we’ve interviewed recommend looking at the

kind of carbs you’re eating, and cutting back on simple carbs. These are the

carbohydrates that break down quickly in the body, sending a rush of sugar into

your bloodstream.

Simple carbs include but aren’t limited to:

- Fruit juice and sweetened beverages such as soda

pop

- Candy

- Pie, cake, cookies, donuts, and the like

- Table sugar and syrup

- White rice

- White bread

- White flour

Packaged foods with words that end in “ose” on the nutrition label, particularly if the “ose” words are close to the beginning of the list of ingredients, are a no. The “ose” words are chemical names for sugar and include words such as glucose, maltose, sucrose, dextrose and, well, you get the idea.

Simple carbs can be found occurring naturally in foods such as milk, fruit, and vegetables. They still raise blood sugar levels faster than complex carbs, but they’re better for you, as they have fiber and other things your body needs. They’re not empty calories like candy, which does nothing for the body but add weight.

Complex carbs will send sugar (fuel) into your bloodstream,

but at a slower rate, giving your body a chance to use up some of the sugar

before it overloads the body.

You don’t want to completely remove carbs from your diet.

You want to eat complex carbs and leave as many simple carbs as possible on the

table.

Complex carbs include but aren’t limited to:

- Whole grain breads

- Quinoa, and brown or wild rice

- Sweet potatoes, pumpkin, and squash

- Beans and pulses (the dry edible seed inside a

pod, such as chickpeas, lentils, and dry beans)

- Plain popcorn

What we’re hearing from dietitians is that carbs are OK as

long as they’re not simple carbs, and you don’t consume large amounts of any

carbs. After all, both simple and complex carbs are sugar.

Your body only needs so much fuel each day. If you

constantly overload it, diabetes may be in your future.

The exact number of carbs you should eat will depend on your body. Choose a number and if your meter is showing your fasting blood sugar remains in the prediabetes range, try reducing your daily intake of carbs.

Of course, exercise is part of the lifestyle overhaul, but the key is adapting your way of eating toward healthier choices.

A Healthy Way of Eating: Getting There From Here

The Mediterranean diet, or way or eating, is considered a

healthy choice by almost everyone who has an opinion.

It’s more plant-based than meat lovers are used to, but it is healthy and it does include some meat, so not to worry.. The trick is figuring out which Mediterranean diet to follow.[4]

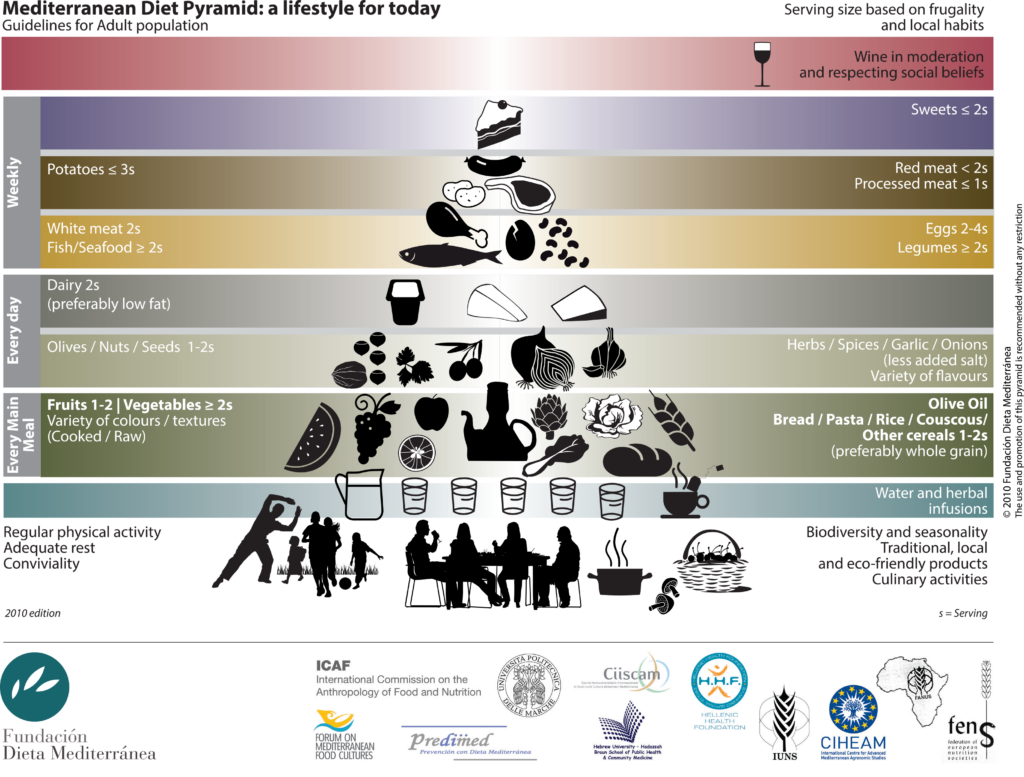

The following food pyramid is from the Mediterranean Diet Foundation.[5] Note that the grains and cereals should be whole grain for prediabetics, and the daily serving (noted as “s”) may be less for those living with prediabetes.

You don’t have to put a name to your way of eating. As long as you’re watching your total calories per day and choosing complex carbs over simple carbs, you’ll be ahead of the game.

If you don’t have access to a computer and the Internet, or a smartphone or tablet, then a book will be your best friend when you’re counting carbs, calories, and other nutritional info.

The CalorieKing® publishes a book to accompany its website. We came across the website a few years ago and only recently became aware of the book. [We’re not associated with this company—we just like the tools they offer.]

Thanks to computers and smartphones, there are easy ways to

find out how many carbs, calories, proteins, and fats are in whatever you want

to eat. Almost.

We’ve used the CalorieKing®, website, although there are lots of similar websites that provide the same information. Choose one that suits you best.

If you use apps, there are loads of them. We like Carb

Manager. They have a free version and a premium option, as do most apps. [We’re

not associated with this company, either.]

It’s an app we use and like, but please ignore the “keto”

and “low carb” slogans they use. This app has all the nutritional information

you’ll want to find sensible, healthy choices for yourself and it doesn’t

matter if you’re following a specific way of eating or simply sampling foods.

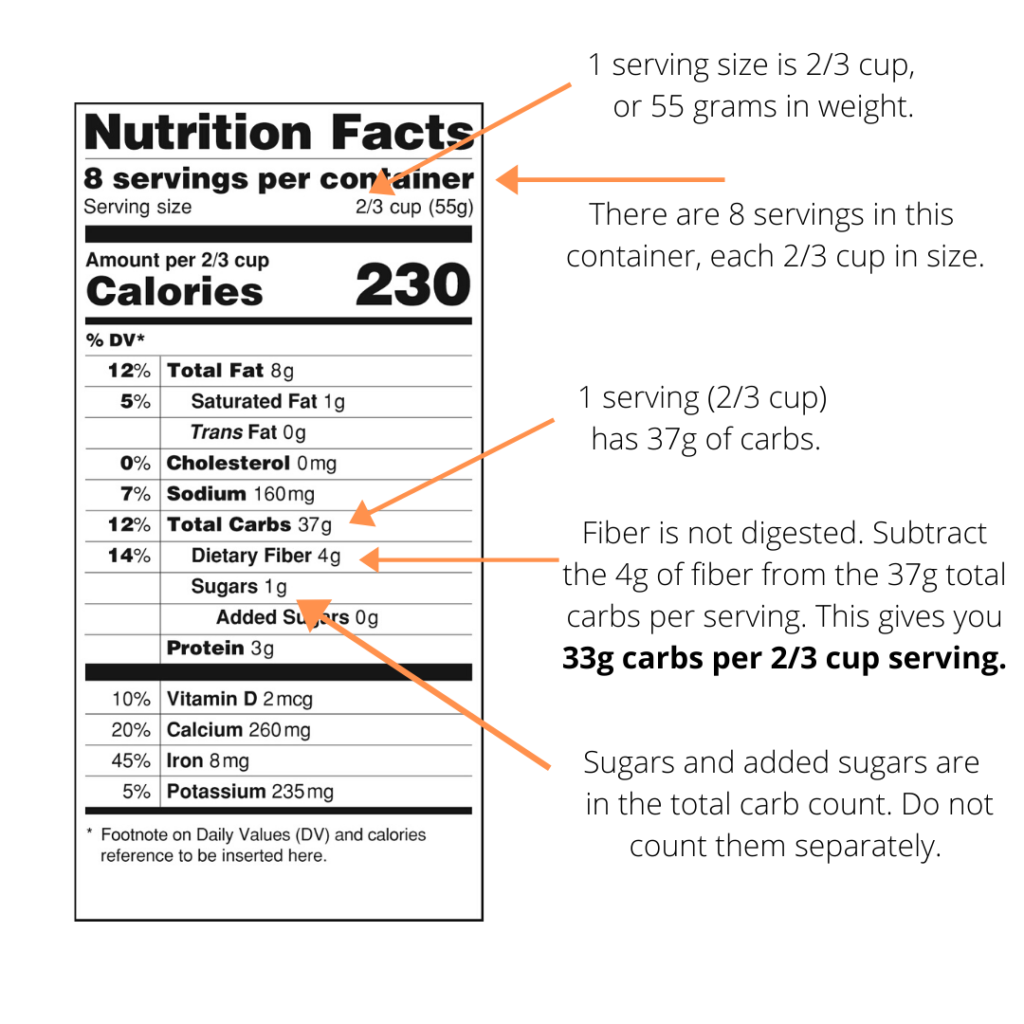

Whether you’re using a book, a website, or an app, the

process is the same. Search for the food you want to eat, let’s say apples, and

you’ll find out how many carbs and other nutrients are in a serving. You’ll

also find out what constitutes a serving size.

Apps are ideal, because they track all of your food all day and you don’t have to write anything down. But books and websites give you the critical information, and some websites let you set up an account to track your food, the same as apps on your phone.

We’ve been culling through recipes to offer an assortment

that lean toward complex carbs rather than simple carbs, and perhaps slant

toward the Mediterranean.

Circle back in a week or so and we’ll have started our

recipe section.

[1]

Annals of Family Medicine, Prevalence of

Prediabetes and Abdominal Obesity Among Healthy-Weight Adults: 18-Year Trend,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4940459/,

(February 5, 2020).

[2]

MedlinePlus, Prediabetes, https://medlineplus.gov/prediabetes.html,

(February 6, 2020).

[3]

Diabetes Care, Nutrition Therapy for

Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report, https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/42/5/731?fbclid=IwAR187_GK6JXI_i2JW1ZW4TT3a6Hu0D2N4rcwgGg2qd0KpQtGz2XGKPXPkPk,

(February 6, 2020).

[4]

Nutrients, Definition of the

Mediterranean Diet: A Literature Review, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4663587/,

(February 7, 2020).

[5]

Mediterranean Diet Foundation, Mediterranean

Diet Pyramid: a lifestyle for today, https://dietamediterranea.com/piramidedm/piramide_INGLES.pdf,

(February 7, 2020).